Telluride – City of Lights

Mining, Millionaires, and City of Lights

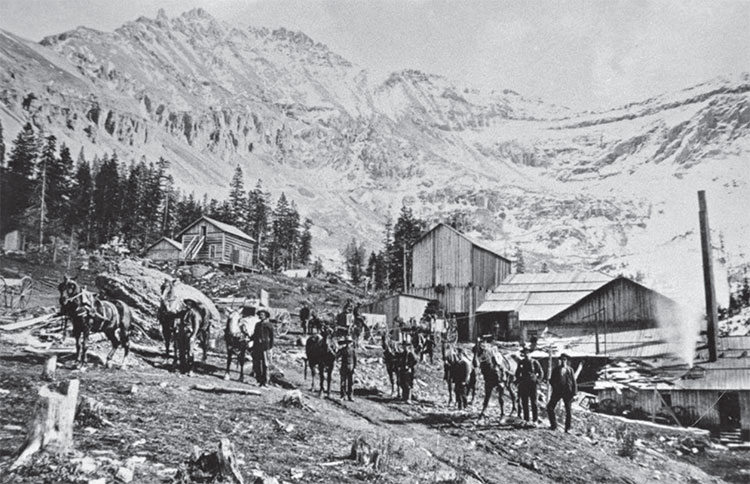

Telluride the City of Lights. It was the late 1880s, and mining in Telluride was in its heyday. The town had more millionaires per capita than any other place on earth. Otto Mears’ new toll road (the Million Dollar Highway) provided more accessible access to markets hungry for Telluride’s gold and silver. Grand houses were popping up on Columbia Avenue, and gold coins were piled in two-foot-tall stacks in Telluride’s banks – lucrative enough to attract the attention of Butch Cassidy, who robbed his first bank right here on Colorado Avenue in 1889. Mining Needs Cheep Power

Mining Needs Cheep Power

But this self-styled “Town Without a Bellyache” was starting to show signs of indigestion. As the easy-to-mine surface ore dried up, extraction costs began to climb. Transporting the ore for processing elsewhere no longer made financial sense, so mining companies built mills close to their mines and powered them with wood-fired steam engines. Before long, however, the slopes above Telluride were almost devoid of trees, so the mines began packing in coal by burro. The cost was prohibitive, with fuel bills topping $2,500 a month. It was expensive even by today’s standards, and the more remote mines started to fail. The problem of supplying Telluride’s mines with an inexpensive power source seriously threatened the entire region.

Nunn, the Big Dreamer

As with many pivotal moments in Telluride’s history, the day was saved by a colorful character who was not afraid to dream big. In this case, his name was Lucien L. Nunn. Not your obvious choice for a hero, Nunn barely topped 5 feet tall. The Ohio native had studied law in Germany and Massachusetts before the romance and potential of the American West drew him to Colorado. Two failed restaurant ventures later, Nunn landed in Telluride, feeling washed up at the ripe old age of 28. Pinheads

Nunn may have achieved long-distance transmission of AC electricity, but next, he needed engineers to run the dang thing. He turned to Cornell University, enticing electrical engineering students to the San Juans. His self-styled Telluride Institute gave these youngsters a place to brainstorm solutions, develop new equipment, and gain hands-on experience before they moved on to new jobs elsewhere in the West. Nunn marked their subsequent movements with pins on a giant wall map, earning his engineers the moniker of Pinheads. It’s a name that lives on today with the Pinhead Institute, the local non-profit, and Smithsonian Affiliate that promotes science education.

Mythbuster

A local tall tale revolves around the Bridal Veil Hydroelectric Power Plant, perched in the east end of the box canyon at the top of Bridal Veil Falls, Colorado’s tallest free-falling waterfall at 365 feet. The story goes that the plant at Bridal Veil is the second oldest hydroelectric power plant in the world but that doesn’t seem to be true as the plant wasn’t operational until 1907. By this time, many other plants were generating power using water.

Telluride Folklore

Other folklore has it that the town was the first in the world to have electric streetlights. Alas, this is likely not true either. It seems that by the late 1870s more than a few cities were illuminated by electric lights – earlier than 1892 when Telluride first flicked the switch.

Wired

After the electrification of Gold King, Nunn acquired new mines, including one in Bear Creek Canyon. To transmit power there, he ran a line from Ames, up and over the peaks of the present-day ski area and into Bear Creek, and eventually into town and the basins and mines to the north. Some original wiring, power plant artifacts, and photographs are on display at the Telluride Historical Museum. The present-day ski run “Powerline” partly follows Nunn’s route.

Pinheads

Nunn may have achieved long-distance transmission of AC electricity, but next, he needed engineers to run the dang thing. He turned to Cornell University, enticing electrical engineering students to the San Juans. His self-styled Telluride Institute gave these youngsters a place to brainstorm solutions, develop new equipment, and gain hands-on experience before they moved on to new jobs elsewhere in the West. Nunn marked their subsequent movements with pins on a giant wall map, earning his engineers the moniker of Pinheads. It’s a name that lives on today with the Pinhead Institute, the local non-profit, and Smithsonian Affiliate that promotes science education.

Mythbuster

A local tall tale revolves around the Bridal Veil Hydroelectric Power Plant, perched in the east end of the box canyon at the top of Bridal Veil Falls, Colorado’s tallest free-falling waterfall at 365 feet. The story goes that the plant at Bridal Veil is the second oldest hydroelectric power plant in the world but that doesn’t seem to be true as the plant wasn’t operational until 1907. By this time, many other plants were generating power using water.

Telluride Folklore

Other folklore has it that the town was the first in the world to have electric streetlights. Alas, this is likely not true either. It seems that by the late 1870s more than a few cities were illuminated by electric lights – earlier than 1892 when Telluride first flicked the switch.

Wired

After the electrification of Gold King, Nunn acquired new mines, including one in Bear Creek Canyon. To transmit power there, he ran a line from Ames, up and over the peaks of the present-day ski area and into Bear Creek, and eventually into town and the basins and mines to the north. Some original wiring, power plant artifacts, and photographs are on display at the Telluride Historical Museum. The present-day ski run “Powerline” partly follows Nunn’s route.

Nunn, the Businessman

What Nunn lacked as a restaurateur, he made up for as an astute businessman. He eventually amassed a controlling interest in the local bank and ownership of a newspaper. He also bought several prominent buildings, including his home – a large mansion famous for its bathtub, the biggest in town.Nunn, the Mine Owner

Nunn also owned a share of the Gold King mine. The mine sat at an altitude of 12,000 feet, high in the mountains south of Telluride, not too far from Alta Lakes. As he and his fellow stockholders fretted over the problem of a cheap, sustainable source of power for the mine, Nunn was aware that some of the other mine owners in the area – like J.H. Ernest Waters of the Sheridan Mine – had begun to use the Thomas Edison-championed direct-current electricity. But DC was expensive and tricky to transmit over long distances. It wasn’t going to solve Nunn’s difficulties up at Gold King.City of Lights - Tesla - Alternating-Current Electricity

Meanwhile, back east, a young inventor named Nikola Tesla was busily conceiving of alternating current. This format caught the attention of George Westinghouse and directly challenged Edison’s direct-current power. Alternating-current electricity, its adherents reasoned, would ultimately prove superior. Although the generation of AC required a turbine or flowing water, it was more suitable for transmission over longer distances because of how its current traveled. The more Nunn learned about this new-fangled alternating current, the more he was convinced that he was on to a winner.Nunn's Water Rights and Proximity

Other factors combined beautifully to bring Nunn’s notions about AC electricity from hunch to reality. For example, Gold King was remote, but it was just two and a half miles from the Howard and Lake tributaries of the South Fork of the San Miguel River, and Nunn held the rights for both waterways. Also, Nunn arranged for his brother, Paul, a high school science teacher, to work with Westinghouse himself on a solution. And, just as Nunn began to wonder where he would find the cash to fund his evolving plans, the miners who leased the Gold King hit a rich vein of ore worth $2 million, giving Nunn the needed funds.Tesla Motor Powder by Water

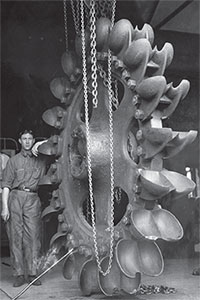

Before long, Nunn had a Westinghouse generator and a Tesla-designed motor set up in the newly constructed Ames Power Plant in Ilium. Two strands of copper wire ran uphill from the plant for almost 3 miles and 3,000 feet to Turkey Creek Basin, where the motor at the mine waited to be powered. At the same time, flumes and pipes channeled the rushing waters of the Howard and the Lake downhill. On June 21, 1891, as local historian David Lavender describes in The Telluride Story, “the Nunns turned a powerful jet of water against a big Pelton wheel belted to the generator. The wheel jumped alive, the lights went on in the station, the wires hummed, and the engineer in charge of the motor at the mine, 2.6 miles away, telephoned down that the motor was turning, too, in perfect synchronization with the generator.” The City of Lights came alive!First Long-Distance of AC Electricity - in Telluride - City of Lights

And just like that, the world’s first long-distance transmission of AC electricity was achieved in tiny, remote Telluride, a town established fewer than 15 years before this historic event. Telluride became the first City of Lights.By Erin Spillane